The proud ‘peasant’ selling £3,000 jumpers to Hollywood royalty

If you’ve never heard of Brunello Cucinelli, chances are you can’t afford him. The Italian designer to the super-rich, he has built a €6 billion luxury clothing empire that dresses people so high in the social stratosphere that they’ll happily part with £3,000 for a jumper.

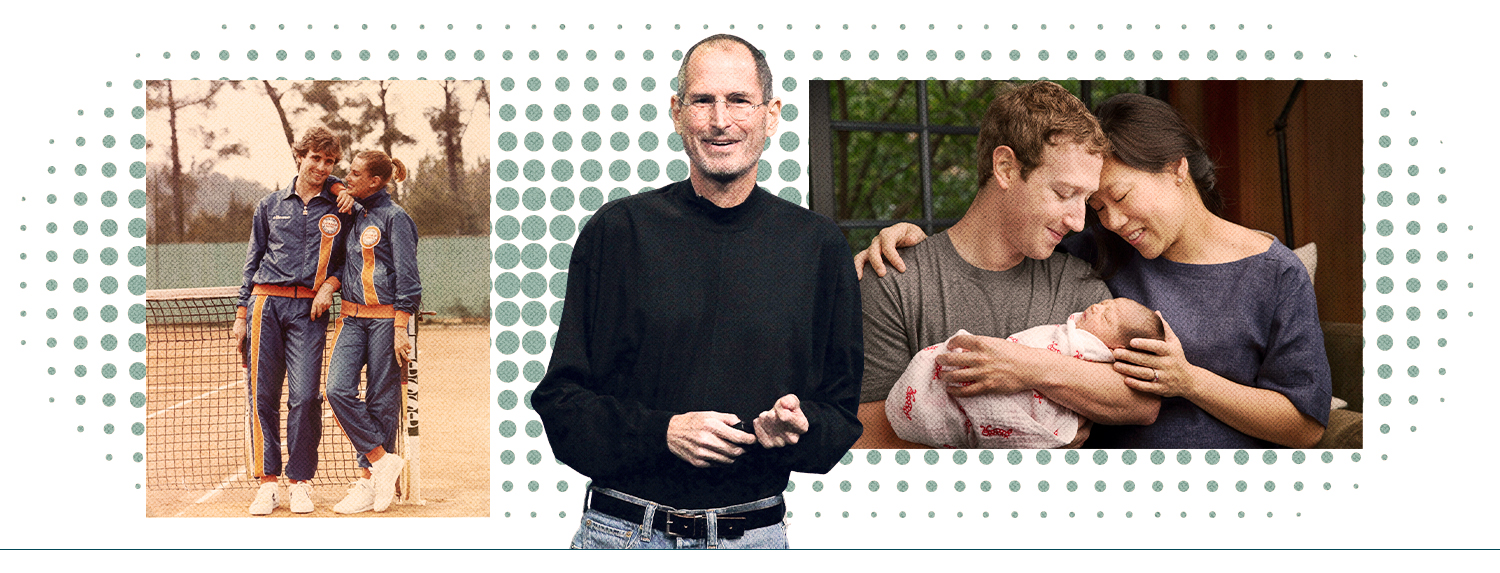

Pronounced “coochinelli”, the founder of the eponymous company is as pally with real royals — Charles, for one — as he is with the royalty of Silicon Valley. The late Steve Jobs’s trademark black turtleneck? Cucinelli. Mark Zuckerberg’s classic grey T-shirt? A £390 Cucinelli.

In womenswear, think the quietly understated cashmere draped on Shiv Roy in the TV series Succession, or the whispered elegance of another Cucinelli chum, Gwyneth Paltrow.

You get nothing so gauche as a logo with this brand, but those in the know, know. “It is,” as one devotee at Goldman Sachs quipped to me over lunch last week: “What you wear when you’re walking on the tarmac from your limo to your private jet.”

Perhaps only Loro Piana and Hermes can claim similar elevated status in the world the fashion press call “quiet luxury”.

While lesser labels — Burberry, in particular — have been struggling amid a cost of living crisis and slow demand from China, Cucinelli has kept churning out the highest quality profit growth for its shareholders on the Milan stock exchange. In its recent half-year figures, the company posted 19 per cent profit growth to €105 million and a 14 per cent increase in turnover to €620.7 million.

The fact is, customers who happily drop £3,200 on the cotton men’s jacket currently featuring on the company’s website, never really feel the pinch, no matter how the rest of us are faring.

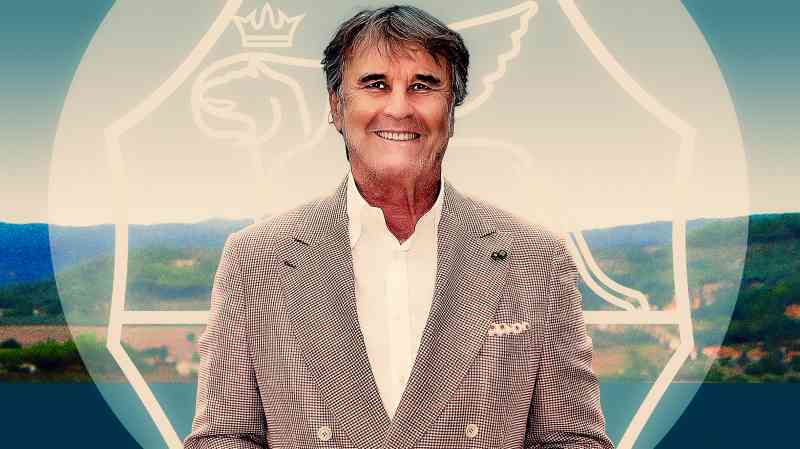

Given the discreetly loaded nature of his clientele, and the business he’s in, you might expect him to be a snooty type. But when he spies me across the hushed lobby at his HQ in the Umbrian countryside, he is anything but. “Ah!” he bellows, in loud Italian: “He is wearing a tie! Ha ha! Of course, how English!”

All in white, with a slim-cut, open-neck shirt and tapered cashmere cords that stop just above the ankle, within seconds he’s on me, fingering the material of my suit, praising its midnight blue colour while theatrically grabbing my shoulders, then shaking my hand. It’s like being jumped on by a six-foot Italian puppy dog.

The interpreter struggles to keep up as he enthuses about all things English, going faster than the beloved Bentley GT he drives down the hill to work in every day.

And what a hill that is. Cucinelli lives in a grand house in a medieval hilltop village in Umbria, a region famed for its knitwear industry. A cluster of caramel-stone houses around an ancient castle, this is Solomeo, a place he has made a key part of the Cucinelli brand.

His daughters, Camilla and Carolina, and their husbands, Riccardo and Alessio, all work in the business and live in handsome homes a few yards away with their children. They are all intimidatingly beautiful.

Solomeo, the home town of his wife (the pair were teenage sweethearts), had fallen on hard times until Cucinelli started to make serious money. When he floated his company in 2012, he cashed in €150 million and spent the lot renovating the area. Not only did he start doing up Solomeo itself, but he bought up the dilapidated industrial buildings in the valley below to return the land to nature.

“I said to my daughters: ‘This valley, it’s beautiful. We have to clean it out and turn it into orchards, vineyards. But it will mean we are €150 million poorer,’ and they said: ‘Yeah? Why not?’

The results are glorious. From the old castle tower that he uses as an office, to the hall he’s turned into a college teaching youngsters tailoring and other crafts, Solomeo is immaculate.

The valley looks straight out of a renaissance painting. “E vero, Of course,” he says, “Perugino [the 15th-century artist who taught Raphael how to draw], painted here.”

With his hand guiding the small of my back, he ushers me excitedly into the large, airy factory downstairs. I say “factory”, but it hardly looks like a factory at all. While there are dozens of Cucinelli-clad men and women stitching, tailoring and pressing garments, it feels more like a trendy open-plan office. Light floods in from huge floor to ceiling windows on all sides, each boasting a view of that delicious countryside.

Cucinelli, a keen student of classical philosophy, is famous in Italy for running his factories as an antidote to the sweatshops of fast fashion. The views, he says, are a key part of that.

“When we moved in, this place had no windows at all,” he says. “Like most factories, the idea was; if workers can see outside they will waste time looking. But that’s not natural. If I have a window and glance out 400 times a day, I waste 500 seconds but I live better. I become more creative as a consequence.”

It isn’t just the windows. Cucinelli’s staff start at 8am and stop at 1pm for an hour and a half lunchbreak, when they eat, for a nominal €3 at the excellent canteen. Then, siesta. “Some go home to see their children, some take a nap, it’s up to them, but in my opinion it’s very important to rest,” he says.

The shift ends at 5.30pm, when it’s home time, with work emails and phone calls strictly forbidden.

He says he pays his workers an average of about €2,100 a month: “That’s 20 per cent more than the average in Italy for this kind of work,” he says, adding that he cannot understand why other companies don’t do the same. When I suggest that’s because most can’t charge £1,000 for a pair of trousers, and outsource to China, he furrows his brow. “I’m not interested in Chinese ways.” The point is, he says, it’s not about the price, but the profit margin; “You know how much it costs me to pay my staff this handsomely? Just 1 per cent of my profitability a year.”

If other companies could sacrifice 1 per cent of their margin to boost their workers’ pay, “it could be a gamechanger,” he says. Cucinelli’s operating margins run at about 16-17 per cent, which is, indeed, lower than many luxury goods companies.

Now 71, he grew up in the countryside nearby. “I am a peasant,” he says proudly. His family were tenant farmers, and he recalls idyllic days helping in the fields. But Cucinelli padre eventually moved them to the city and got a job in a factory. Brunello was 15, and seeing the effect the grim conditions had on his father clearly moulded his approach to his 3,000 employees today. “I heard him complain about being humiliated by his employers. I saw him disappointed, upset, with teary eyes.”

After drifting somewhat in his early twenties, modelling for the Ellesse sports brand and hairdressers who would sometimes send him home with his locks died bright green or red, he had a sudden idea. “It was literally overnight,” he says. Benetton was making a fortune selling brightly-coloured Shetland wool jumpers; Cucinelli figured he could do the same, but with cashmere. Loading his first batch into a van, he hit the road, started selling, and hasn’t looked back since.

So, why is it that Burberry and other fashion brands are going through such tough times, while he is thriving? “I would say that, 12 to 14 years ago, Burberry had the most excellent, top quality product, made in England or made here in Umbria. They had a great way of working, and they had a great image. Then they decided to change, and that was their choice.”

A Burberry spokesman responds that, to the contrary, the brand has been busily bringing manufacturing back to the UK and Europe in recent years.

He has little sympathy for the big fashion houses warning of troubled times. “In 2019 to 2023, those very famous names, they doubled their turnover and raised their profit by 35 per cent. That doesn’t sound like a lot of trouble, does it?

“For us, over the past 20 years we basically grew by 11 per cent on average. That’s normal, not violent growth. If you grow violently, you will fail violently.”

When he floated, his advisers told him if he did not promise to expand the business 20 to 30 per cent a year, nobody would buy the shares. “I said don’t even remotely think about that. We want a growth rate of about 10 per cent and that’s that.”

Since then, despite a sharp fall along with the rest of the sector since spring, the shares are up 617 per cent even after a 5 per cent drift down since the start of the year. He and his family own roughly half of the shares, and the company’s market value is €5.66 billion.

His friend Sir Paul Smith puts Cucinelli’s success down to focus. “He’s the perfect example of beautiful quality Italian clothes. It’s a very complete style and doesn’t differ from that,” he says.

Paul Smith, like many other UK luxury brands, has been held back in Britain by the end of duty free shopping. Have Cucinelli’s London stores suffered? He shrugs: “For us, the UK is doing well. The duty-free issue does affect us a little, but the kind of target customers we have, even if they do not get their tax back, it’s not really an issue for them.”

We walk out into the sunshine, where a fountain is playing by a statue of the god Hermes. Is it a nod to the similarly named Parisian luxury rival? Not at all, the billionaire responds, “He’s the god of trade and commerce.” As we walk past, I’m sure I catch it smiling down on him.

Post Comment