How ‘Sir Suspenders’ sealed SoftBank’s deal for UK tech jewel Arm

The morning sun framed Simon Robey’s regal presence like an incandescent halo.

“If you do exactly as I say, you will win,” he said softly, his buttery voice redolent of his days as a choral scholar at Oxford.

Robey occupied a substantial upholstered armchair placed in front of an east-facing window in the sparsely decorated living room of Masayoshi Son’s rental home, a French Revival-style stone manse on a flat acre in the exclusive Silicon Valley enclave of Atherton. An antique stone Buddha, about four feet tall, guarded Robey’s throne, somehow preserving its dignity despite the tragic loss of its nose. Robey’s thumbs were hooked under his black silk (braces) suspenders, and he looked magisterial in his crisp white shirt and navy suit.

He had asked me how he should dress for the meeting, and this was his interpretation of “casual”.

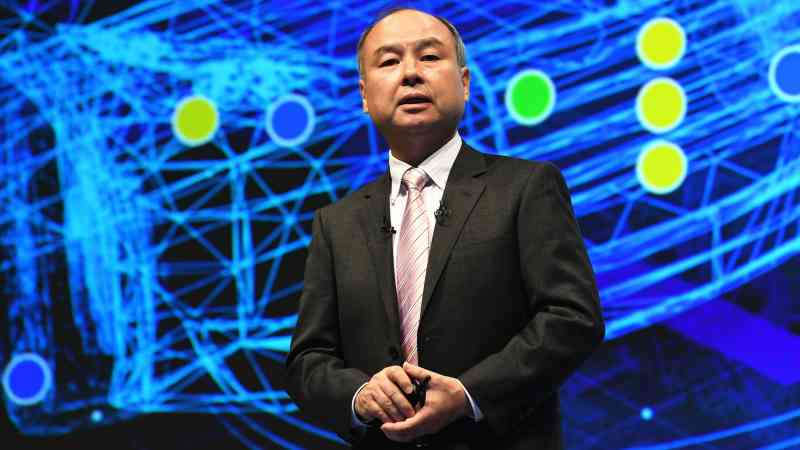

“But you must do as I say,” Robey added sternly, like a schoolteacher lecturing a child on the existential significance of multiplication tables. Except he was addressing Masayoshi Son, head of SoftBank Group, who was perched cross-legged on a sofa across from Robey. I was lounging on a neighbouring couch and marvelling at the pliability of Masa’s hip flexors.

It had been over ten years since I had seen my former colleague in action, but Robey had lost none of the chutzpah that had made him Morgan Stanley’s star M&A banker in Europe. He had launched his own boutique advisory firm, and he was now Sir Simon Robey, the title enhancing his patrician aura. He had been knighted a few weeks ago, I had explained to Masa. But when I tried to draw a parallel with his samurai idol Ryōma, Masa seemed offended. “No, that is not like Ryōma. Ryōma was a peasant, a man of the people,” Masa had said.

Masa was looking at Robey quizzically, trying to decide if Sir Suspenders — as he playfully christened him — was smart, stupid or just plain weird. But after navigating $2 trillion of cross-border merger deals over 30 years, Robey was a confident man with a lot to be confident about. M&A specialists are to investment banking what fighter pilots are to combat, and if there was a Top Gun school for dealmakers in Her Majesty’s realm, Robey would be the Dean.

“We need someone like him,” I had explained to Masa. Acquiring Arm Holdings, the crown jewel of British technology, would always be challenging, but in the current environment it was the equivalent of Maverick’s 4G inverted dive with a Mig-28. It was five days after England’s fateful Brexit own goal, David Cameron had announced his resignation, and a wounded London was struggling to rouse itself for the midsummer rites at Ascot, Henley and Wimbledon. But in the world of finance, there is opportunity in every calamity. The pound had taken a hit, making a deal cheaper in dollar or yen terms. And perhaps the new government could be persuaded to view a SoftBank investment as a vote of confidence? We needed an insider to work the quintessential old boy network of Oxbridge-educated civil servants who run the country while the feckless politicians come and go. We needed Robey.

He was reluctant at first. His franchise was based on advising British companies, frequently defending against unfriendly overtures from foreign intruders. Besides, Masa was known to be intractable. I assured Simon I had Masa’s trust, and persuaded him to get in front of Masa and satisfy himself.

Sir Suspenders took us through the subtleties of the City of London’s unique Takeover Code. Like cricket, the spirit of the Code is sacrosanct, and all players in the M&A game, principals and agents, are expected to abide. I’m personally a fan of the Takeover Code, as I am of cricket. The Code eliminates the games people play on Wall Street, frequently to the detriment of the average investor. It pushes a prospective buyer to make a straightforward cash offer — no “funny money” in the form of complex securities — and to clarify intent publicly with limited scope for clandestine negotiations.

Robey affirmed much of what I had already told Masa: be prepared to pay a substantial premium over the £19 billion market value of Arm, have the cash lined up, and get ready to move confidentially and expeditiously. Any formal approach to the company would be directed to Arm’s chairman, who would negotiate on behalf of its shareholders. Robey would work his network to make sure we had the support of key constituencies: the media, the investment community and the various government agencies.

By the time we were done, I could tell Masa was impressed. Robey was no samurai, but you do not bring a baseball player to a cricket match.

After Robey’s clear direction, there was no stopping Masa. I drafted a letter from Masa addressed to Arm’s chairman, Stuart Chambers, outlining SoftBank’s all-cash bid for 100 per cent ownership of Arm, offering each shareholder a substantial premium to the previous day’s closing price, with no antitrust or regulatory contingencies.

In military parlance this was “shock and awe”; in M&A lexicon this was a “bear hug”. A parallel is making an unsolicited bid to buy an unlisted expensive home you had long coveted, but had never viewed from the inside, with no financing contingency. You might find the home termite-infested or be denied the use of the pool, that risk was all yours. And since the owners had no expressed intention of selling, you needed to offer a price well above market value to get their attention.

My keystrokes, as I drafted the letter, were concerningly tentative rather than fondly lingering: in over 30 years of deal-making this was as audacious as I had seen. We were paying a hefty premium over an already inflated price. Should I be restraining Masa? But then again Arm was a terrific global business, with a dominant market share and a protective moat in the form of patented technology. And Masa’s vision for Arm was no crazier than ubiquitous smartphones might have seemed in 2005.

To maximise impact, we agreed the proposal needed to be delivered in person. But Stuart Chambers was on vacation, on a boat in the Mediterranean and unavailable for another two weeks. Masa would have none of it. If Stuart had been on a hiking trip to Tora Bora, Masa would have parachuted in, his trusty valet Kota-san at his side, in full-on Rambo mode to ward off Taliban interference. He inquired if Stuart’s boat was large enough to accommodate a helicopter landing. Mercifully, we never found out.

Stuart agreed to meet us on dry land in the port of Marmaris in Turkey on Sunday, July 3. Lunch was scheduled for 12 noon at the Pineapple Restaurant, and Kota-san was dispatched ahead of time to manage onsite logistics. Masa would fly in on his Gulfstream G650 from Tokyo. SoftBank’s other jet — which I affectionately called Viper — was dispatched to San Jose to pick up Arm’s chief executive, Simon Segars. I would fly in, on a private charter, from London.

And so it came to be that on a midsummer holiday weekend, three days following a terrorist attack in Istanbul that left 45 people dead, local air traffic control would notice three blips converging purposefully on this sleepy backwater of the Turkish Riviera at sunrise, their mission unknown.

Alok Sama is the former president and chief financial officer of SoftBank Group International

The Money Trap by Alok Sama (Pan Macmillan £22). To order a copy go to timesbookshop.co.uk. Free UK standard P&P on orders over £25. Special discount available for Times+ members

Post Comment